London architecture through time

Epochs and echoes – reading London’s history through its architecture

As one of the world’s great capitals, London’s long and illustrious history is reflected by its architecture. Less planned and coordinated in its development than many of Europe’s other great cities, such as Rome, Paris and Vienna, London is a city of extreme urban diversity, with countless architectural gems from every era.

Internationally recognised experts in the revival of buildings, both historical and contemporary, Thomann-Hanry® have worked on many of these wonderful structures and are well-versed in the architectural movements that have combined to shape the cosmopolitan city we see today.

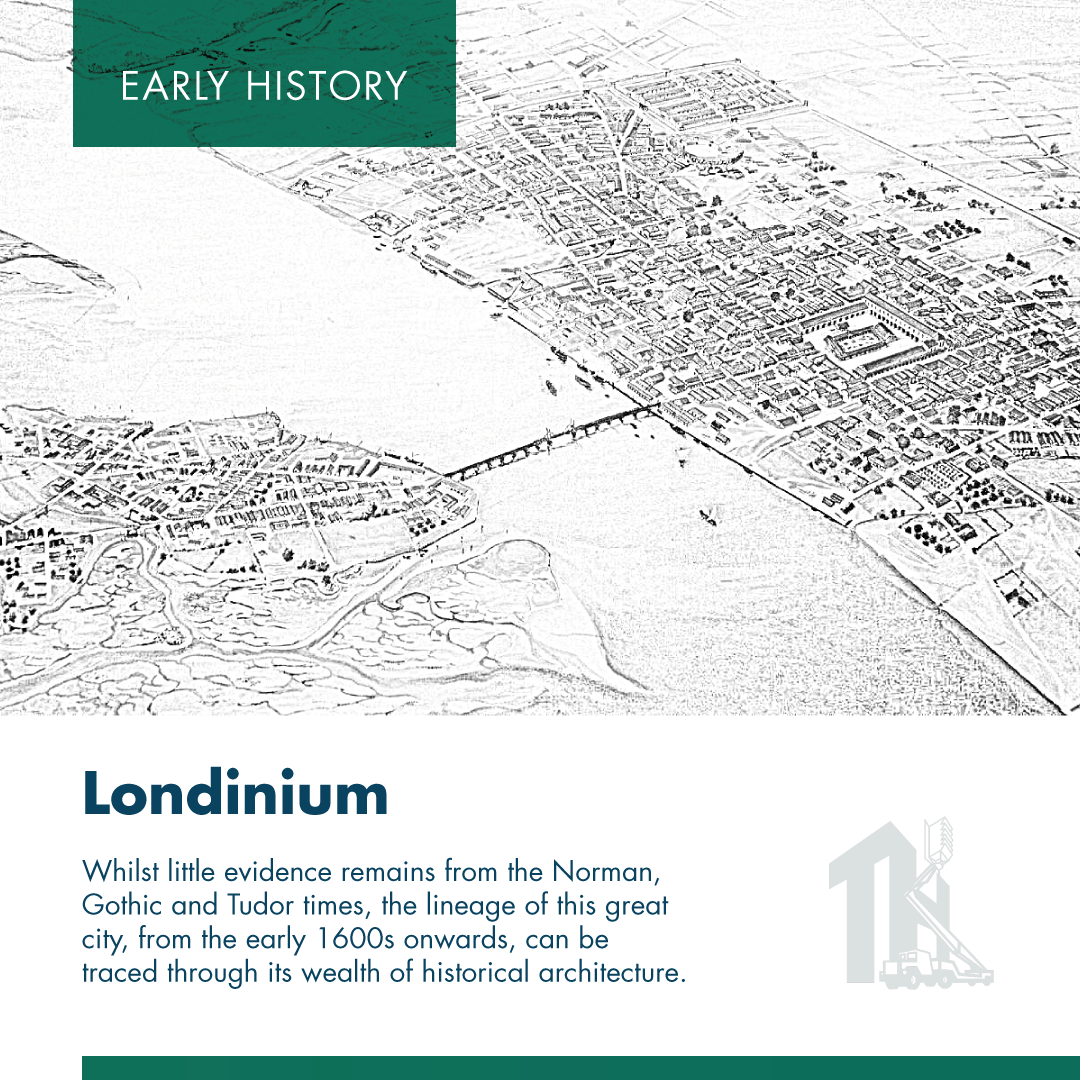

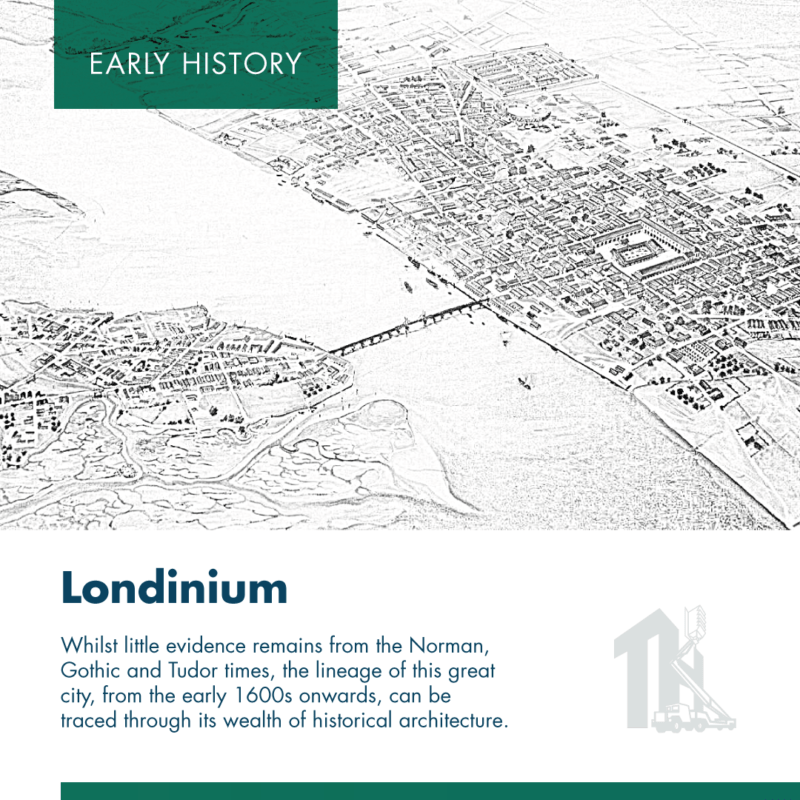

Early history | Londinium

London has been inhabited almost continuously since 43AD, when it was the Roman city of Londinium. After the Romans’ withdrawal in the fifth century, the street layout was adopted as the blueprint for Saxon and medieval London, shaping the topography of what is now the City of London. Whilst little evidence remains from the Norman, Gothic and Tudor times, the lineage of this great city, from the early 1600s onwards, can be traced through its wealth of historical architecture.

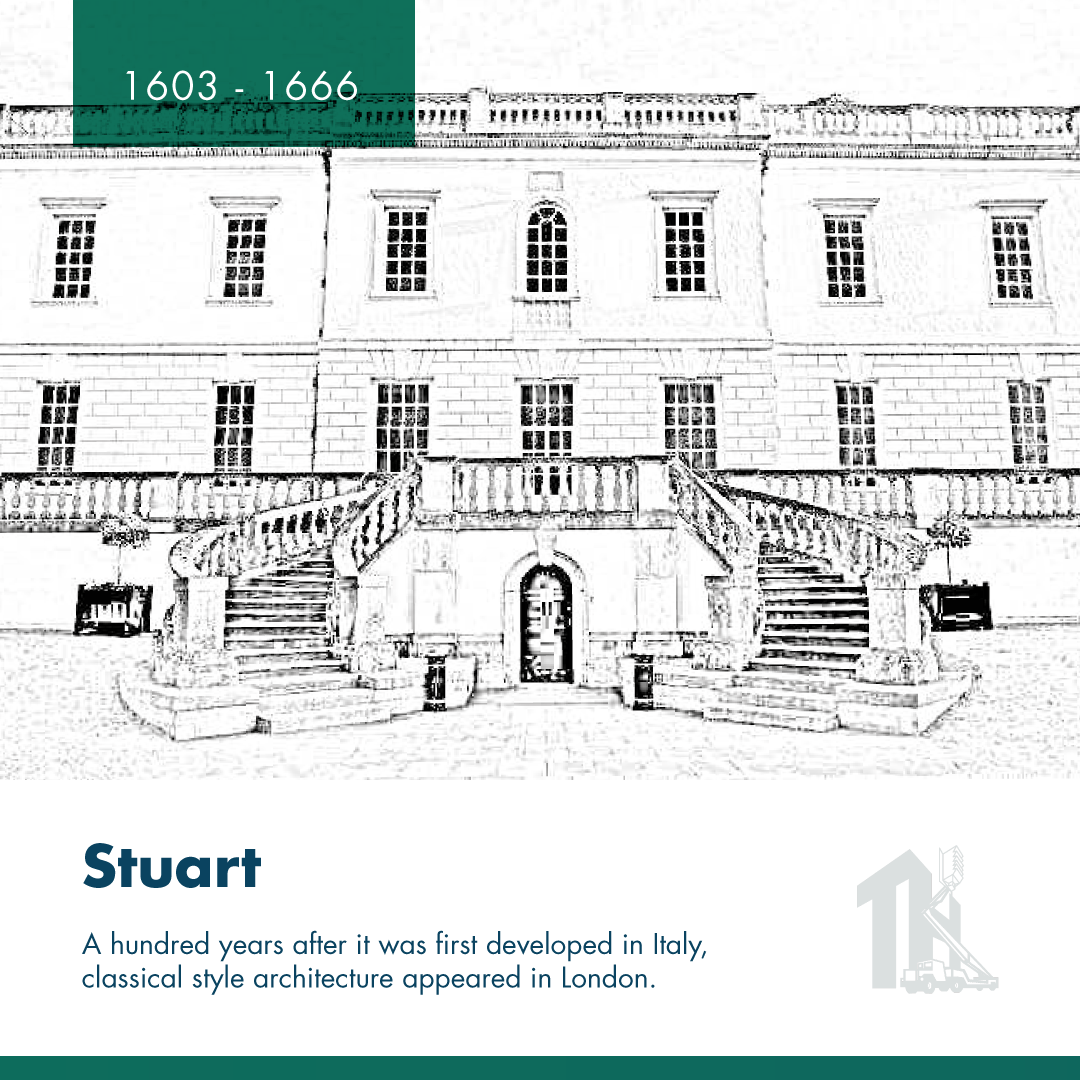

Stuart

1603-1666

A hundred years after it was first developed in Italy, classical style architecture appeared in London. Inspired by the work of Venetian Renaissance luminary Andrea Palladio, Inigo Jones championed classical influences through his designs of some of London’s oldest architectural treasures.

With the Palladian stylings of Tuscan porticos and classical piazzas echoing their Roman origins, early examples include the façade of Banqueting House, Whitehall. Banqueting House was built in 1622 and featured Portland stone, which was to become one of the defining and unifying materials of the capital to this very day.

With its attractive white grey appearance, Portland stone characterises much of London’s architecture and it’s a substrate that Thomann-Hanry® are called upon time and again to clean using façade gommage®, our gentle, dry and non-abrasive cleaning process.

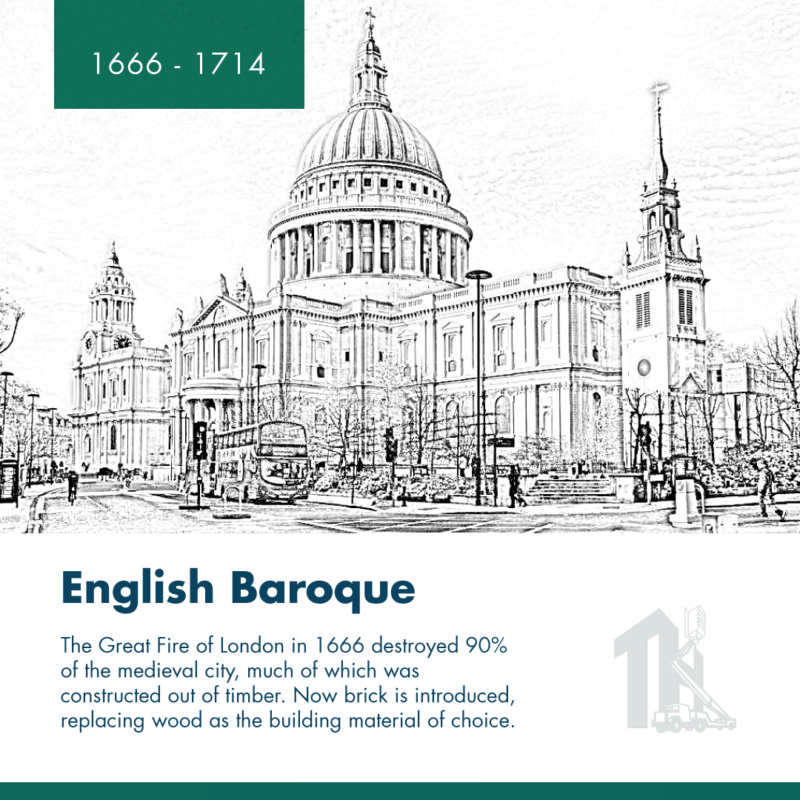

English Baroque

1666-1714

The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed 90% of the medieval city, much of which was constructed out of timber. Grand plans were drawn up to reconfigure the city’s intricate street layout with a grid system and wide boulevards, but these were abandoned due to labour shortages, financial complications and the urgency to re-build.

Instead, much of the medieval street plan was retained, with rows of uniformly proportioned terraces – and brick replacing wood as the building material of choice. Kings Bench Walk, Inner Temple, is a fine example, laying down a blueprint for later Georgian architecture across the city.

As with all brickwork, water-based cleaning is less than ideal, as water can force salts and minerals back into the substrate, simply to return at a later date. Moreover, ancient brickwork dating back to the 1600s, requires even greater care – again, façade gommage® is an ideal solution, gently projecting fine powders under compressed air across the surface to ease off and lift away accumulated dirt and grime.

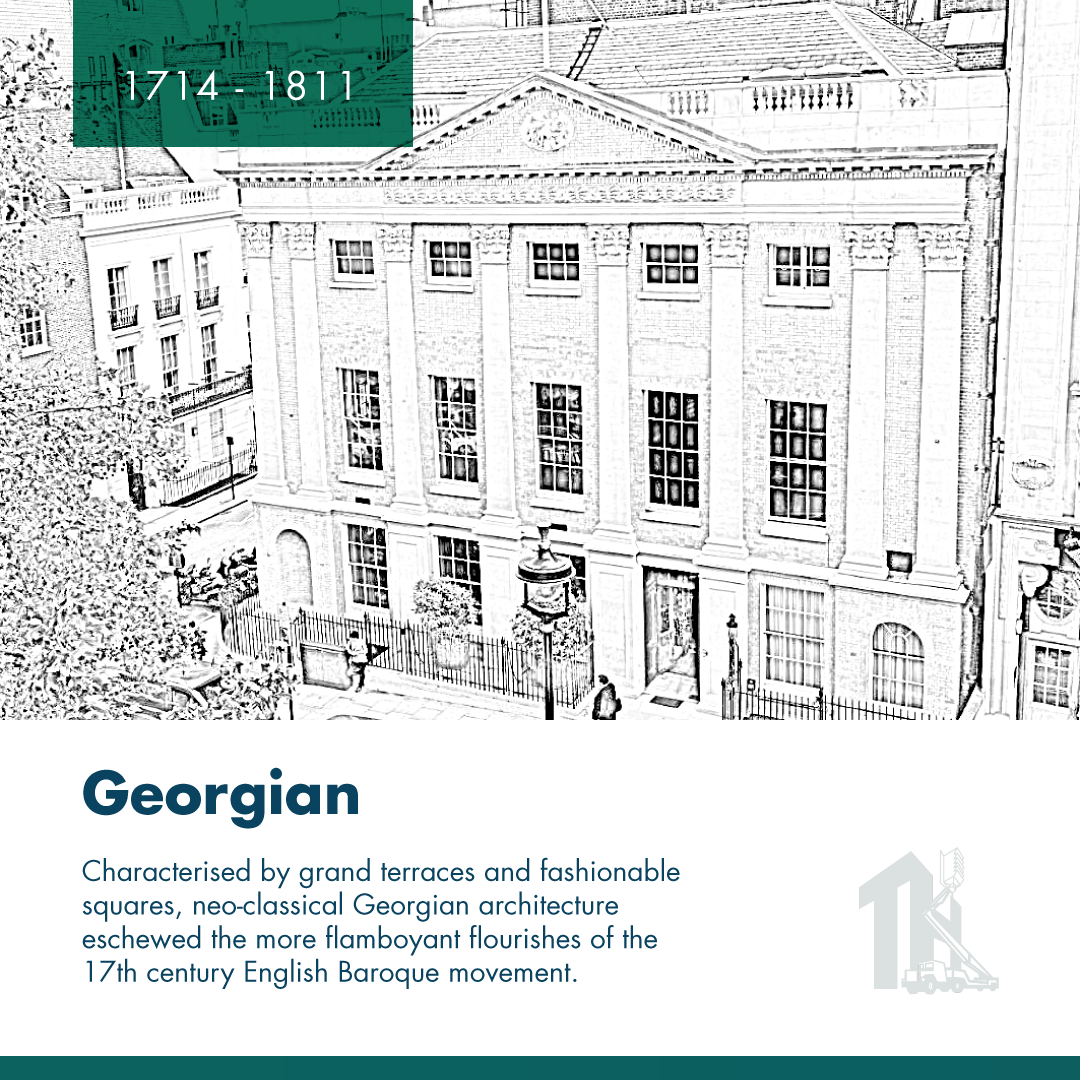

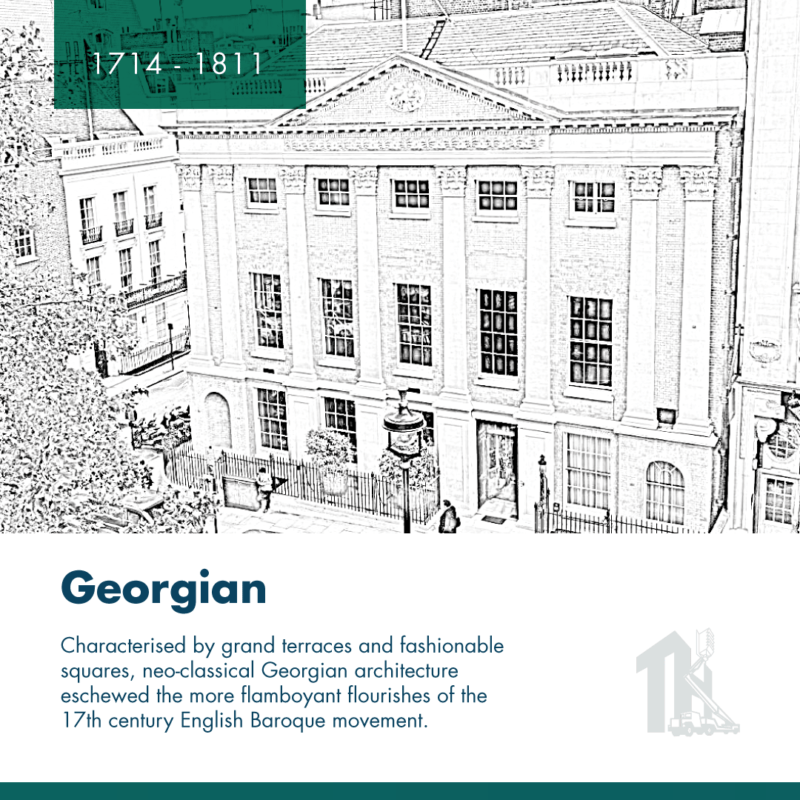

Georgian

1714-1811

As the 18th century progressed and Britain emerged as a global trading power, its capital witnessed sprawling growth, including districts such as Bloomsbury, Marylebone, Mayfair and Kensington.

Characterised by grand terraces and fashionable squares, neo-classical Georgian architecture eschewed the more flamboyant flourishes of the 17th-century English Baroque movement, instead echoing earlier reference points, including the Palladian influences that first appeared over a century earlier.

Many buildings were constructed from buff-coloured London Stock Brick, and geometrical symmetry and restrained ornamentation were favoured. With examples including Downing Street, Georgian architecture is one of London’s most iconic architectural styles, recognised the world over.

Properties featured large sash windows set in triple bay frontages with attic pediments beneath slate mansard roofs. Gauged brickwork, with roofs hidden behind parapets above attic friezes, and restrained use of rustication, pilasters, columns and cornices to indicate wealth and status… Georgian architecture brought neo-classical stylings back to the fore.

On more prestigious houses, brickwork was replaced by imported natural stone or stucco render. As with cleaning other historical building materials, stucco calls for great care – gentle treatment is essential to avoid damaging what can be very fragile surfaces.

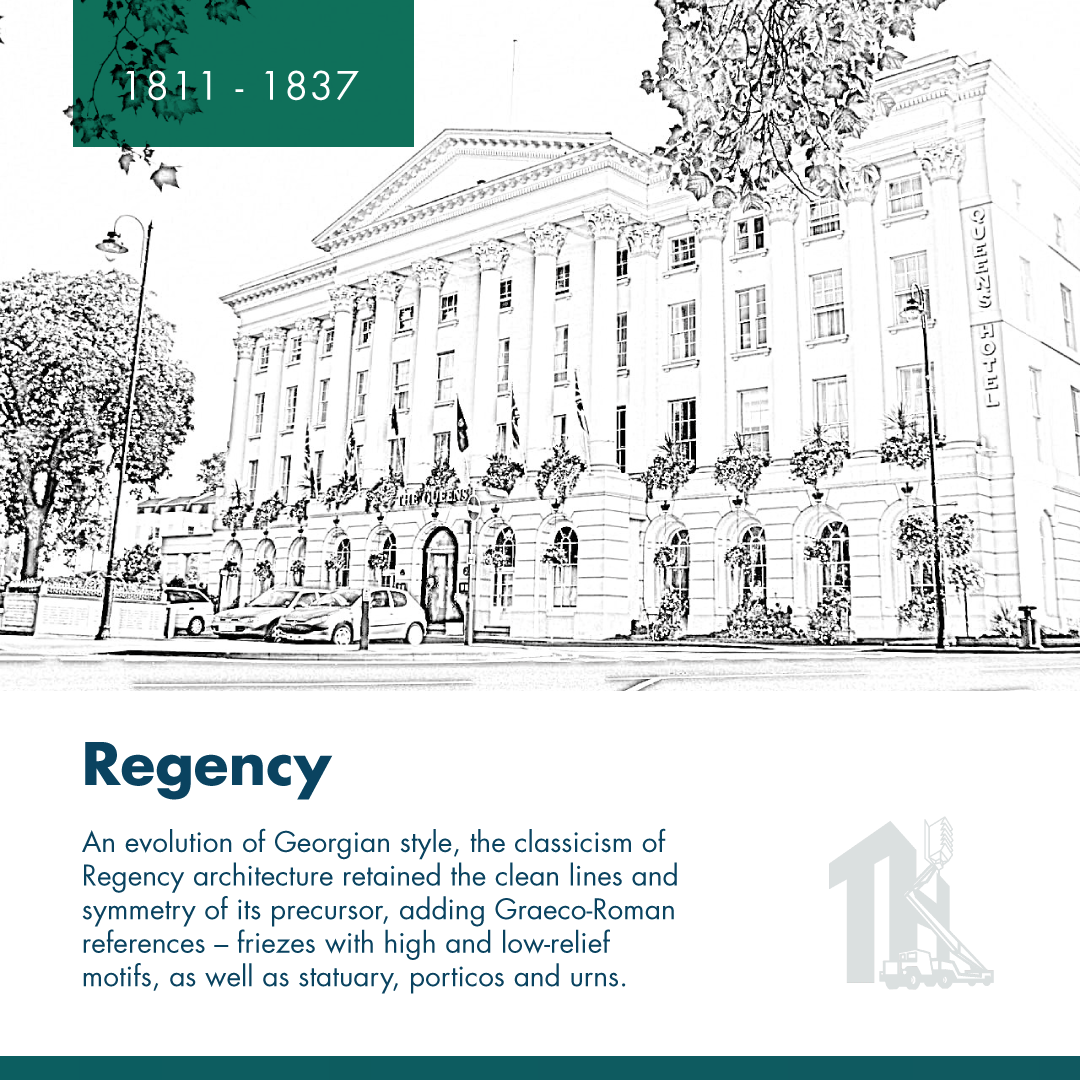

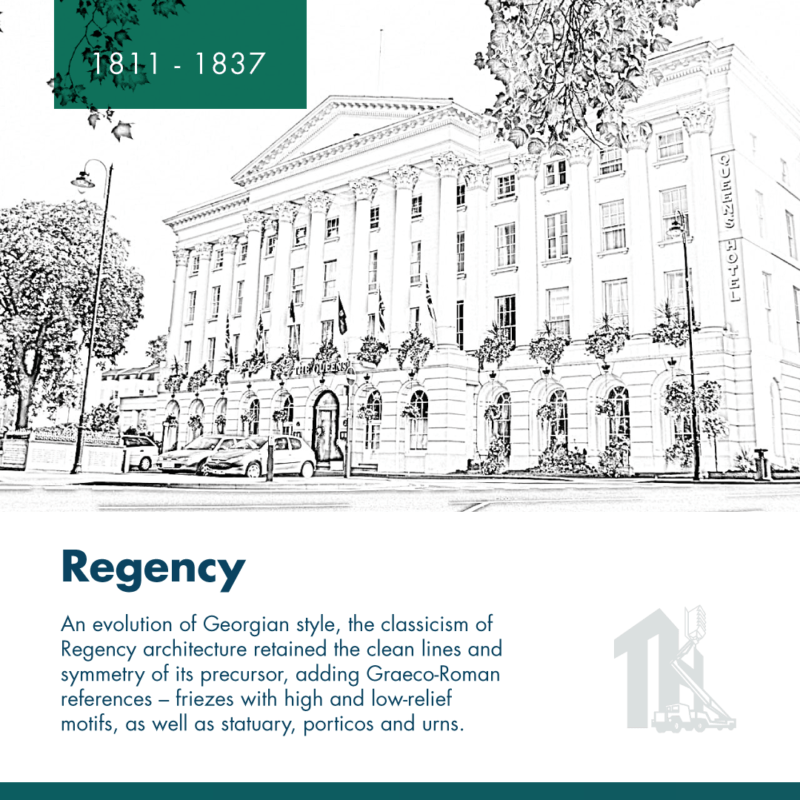

Regency

1811-1837

An evolution of Georgian style, the classicism of Regency architecture retained the clean lines and symmetry of its precursor, adding Graeco-Roman references – friezes with high- and low-relief motifs, as well as statuary, porticos and urns.

The key difference lay in the more extensive use of stucco, which was painted cream to imitate marble and natural stone finishes. With an eye to the bottom line, builders also used stucco to conceal what was occasionally rushed, inferior quality construction. Leading lights of Regency Classicism included John Nash, James Burton and his son Decimus Burton, and their work can be seen in the grand residential terraces around Regents Park. Designed by Decimus Burton, the Athenaeum Club on Pall Mall is a fine example of Regency architecture, with its temple-style frontage, projecting porch, porticos and large pediments.

In what was a short but dazzlingly prolific architectural period, the Regency era produced some of London’s best-known landmarks, from the British Museum, the West Front of Buckingham Palace and Fishmongers Hall to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and the Institute of Directors.

The revival of the capital’s iconic historical structures – as well as its many lesser known buildings from the Regency epoch – calls for careful restoration techniques.

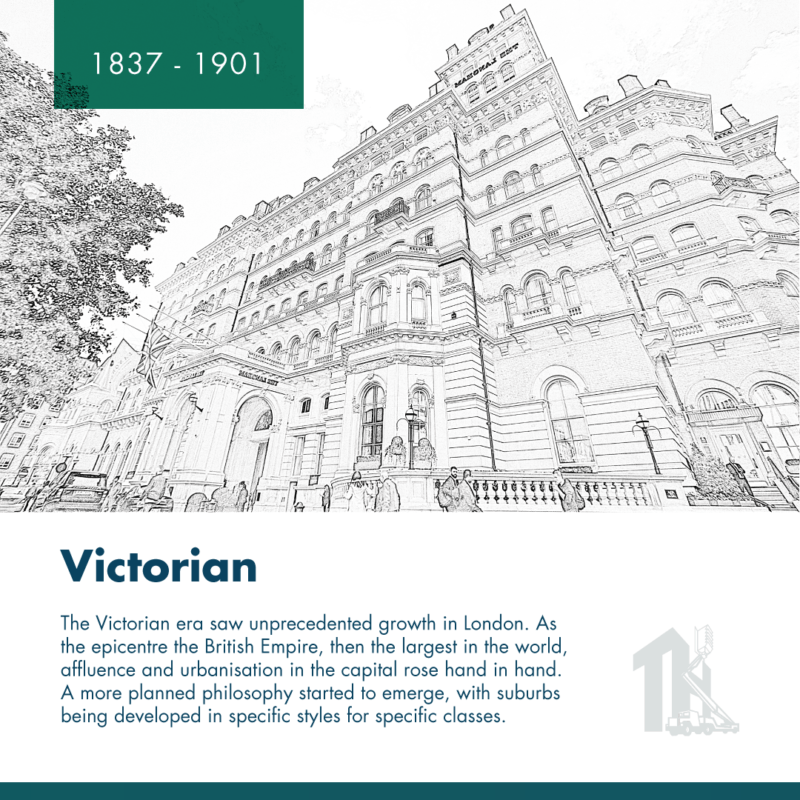

Victorian

1837-1901

The Victorian era saw unprecedented growth in London. As the epicentre, the British Empire, then the largest in the world, affluence and urbanisation in the capital rose hand in hand. A more planned philosophy started to emerge, with suburbs being developed in specific styles for specific classes.

The prevalent style was Neo-Gothic, or Gothic Revival, which coincided with Romanticism, harking back to medieval stylings. Architecture started to adopt more exuberant and ornate detailing, such as tracery, weblike ornamentation on windows and parapets. Symmetrical lines, steep roofs and spires characterised the new breed of building.

The work and influence of John Ruskin and Augustus Pugin were widespread and, in the aftermath of the industrial revolution, new materials like cast iron and steel became increasingly popular. Taking full advantage of the new potential for height and span, notable iron-framed structures included St Pancras Railway Station, a spectacular example of ornamentation and ambition working hand in hand.

The Victorian epoch encompassed a number of other architectural movements, resulting in an eclectic mix of building styles, from Renaissance, Queen Anne and Moorish Revival to Neoclassicism and Second Empire influences copied from the French in the 1870s. Landmarks dating from the period illustrate the eclectic array of architectural movements: the Italianate stylings of the Reform Club; the Victorian High Gothic construction of the Royal Courts of Justice; and the Neoclassic lines of Westminster Bank, to name but a few.

From an architectural restoration perspective, the Victorian era saw the emergence of another new material – terracotta. Increasingly used as a decorative applique from the 1860s onwards, terracotta was favoured as it was colourful and did not absorb the heavy air pollution prevalent at the time. Fine examples include the rebuilt Harrods and the Natural History Museum.

Today, Victorian terracotta is an extremely fragile and friable material, effectively ruling out aggressive water-based cleaning techniques. As a result, Thomann-Hanry® have found façade gommage® to be well-suited to cleaning terracotta surfaces.

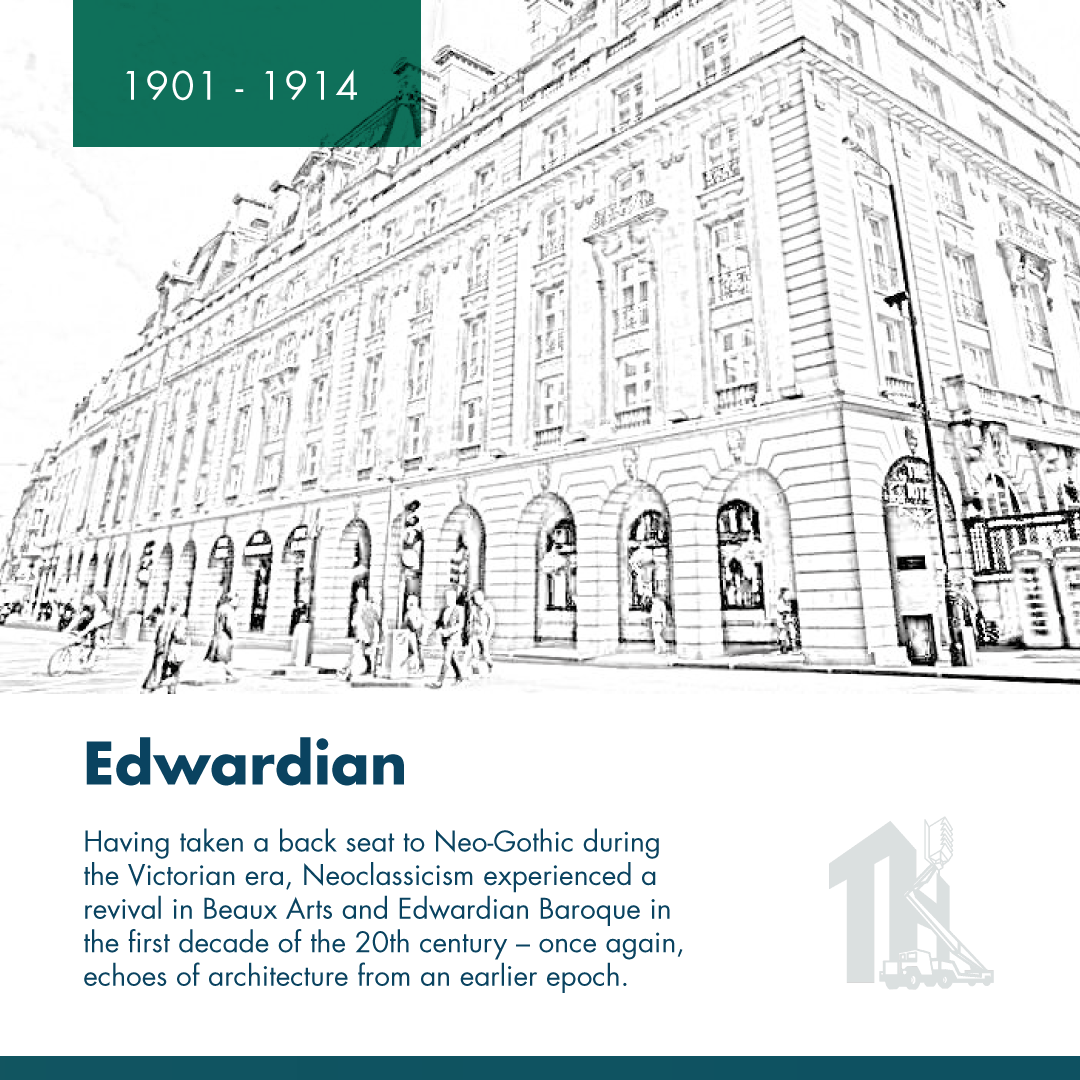

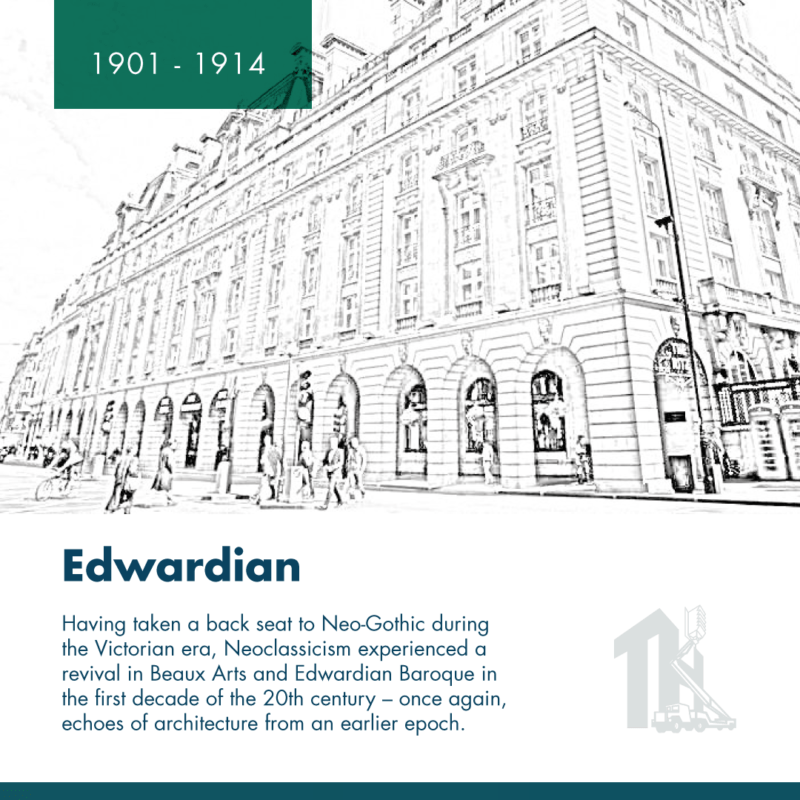

Edwardian

1901-1914

Having taken a back seat to Neo-Gothic during the Victorian era, Neoclassicism experienced a revival in Beaux Arts and Edwardian Baroque in the first decade of the 20th century – once again, echoes of architecture from an earlier epoch.

Epic, monumental structures evoked the grandeur of the Roman Empire, with rusticated stonework, banded and freestanding columns and pilasters with Corinthian or Ionic capitals, and domed roofs and cupolas. Portland stone, eminently suited to such architecture, was widely used – the curving façade of the Regents Street Quadrant being a classic example.

Some of London’s most iconic landmarks were built in the early 1900s – including the Old Bailey, the Ritz Hotel and Selfridges. Another favoured finish during this period was glazed architectural terracotta, also known as “faience”.

More pollution resistant than their predecessor terracotta, these ceramic tiles characterise much of London’s Edwardian architecture, nowhere more so than in underground stations, particularly on the Piccadilly and Bakerloo lines. Further advances in building materials saw the adoption of steel to reinforce larger structures. Widely used in larger public or commercial buildings such as those along Aldwych or Kingsway, steel used in buildings from the first half of the 20th century is the cause of many problems a century later.

Known as Regent Street Disease, corrosion within masonry clad buildings of this nature can cause extensive damage to the fabric of buildings – a frequent cause of remedial works undertaken by Thomann-Hanry®.

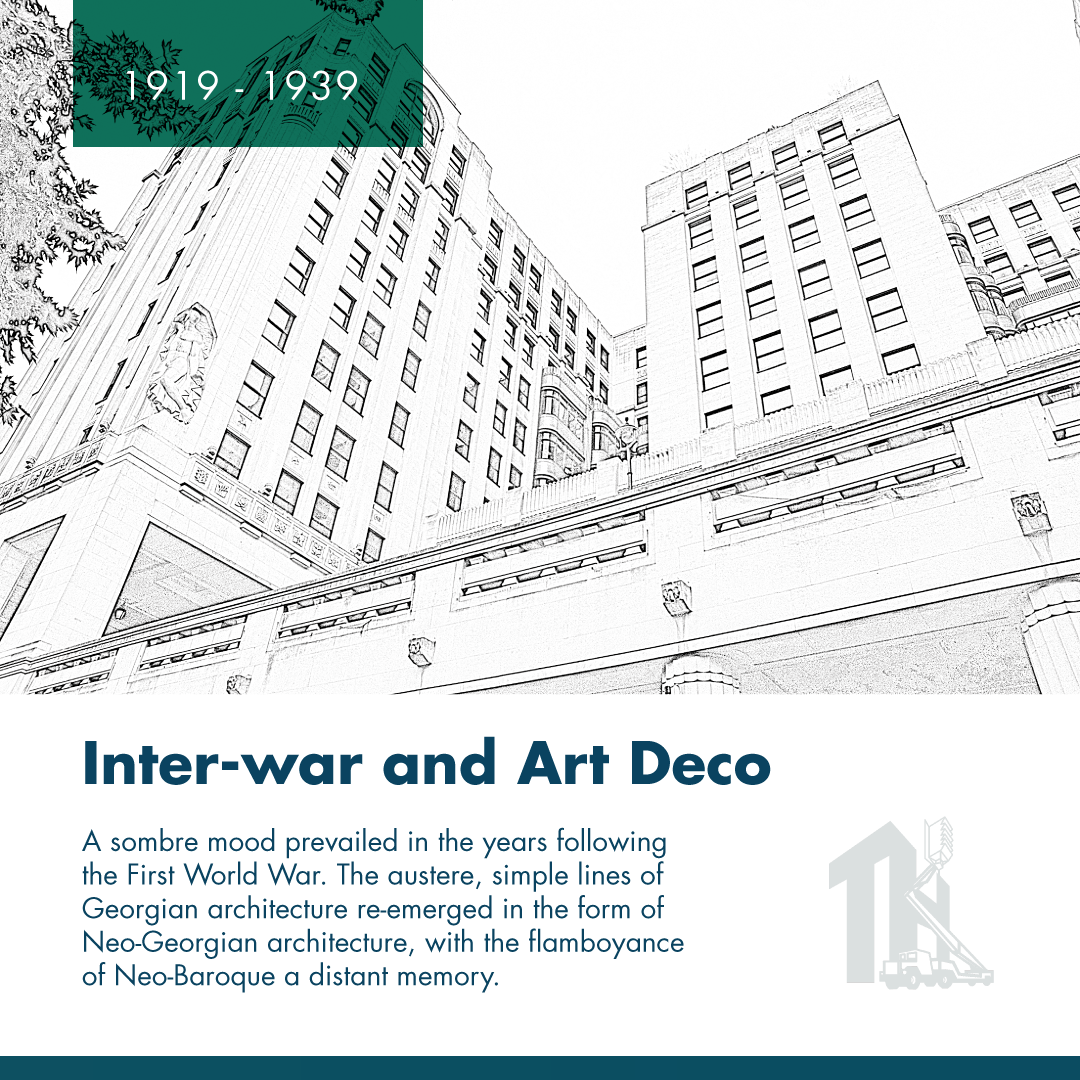

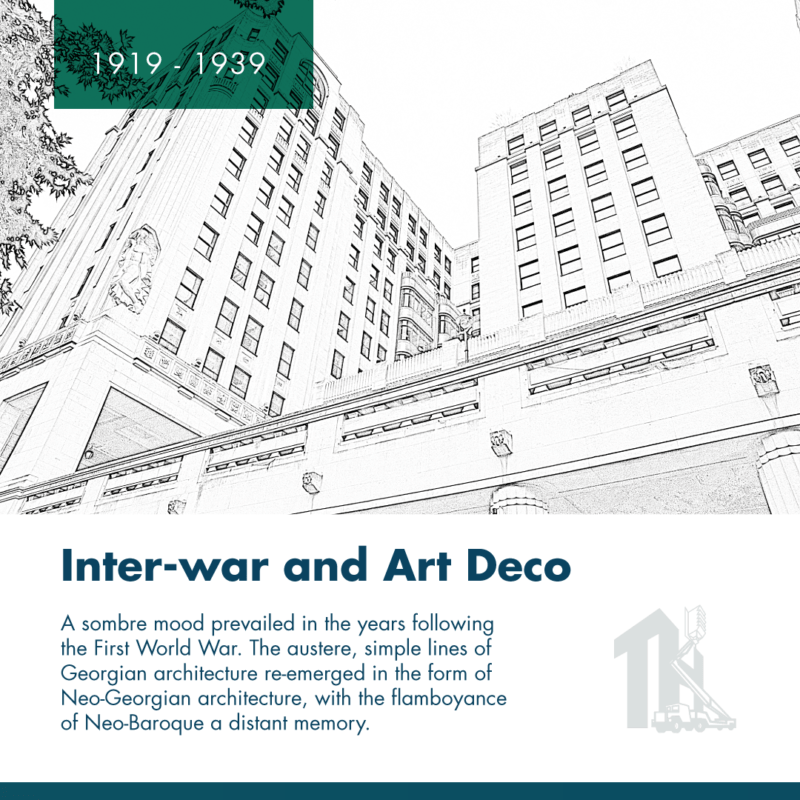

Inter-war and Art Deco

1919-1939

A sombre mood prevailed in the years following the First World War. The austere, simple lines of Georgian architecture re-emerged in the form of Neo-Georgian architecture, with the flamboyance of Neo-Baroque a distant memory.

There was a certain irony in original Georgian houses being demolished to make way for larger Neo-Georgian replacements. Alongside this, Neo-Classicism remained in vogue, particularly on larger projects, such as the Bank of England. Again, Portland stone was widely used, embedding its status as London’s “local stone”. 1925’s International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris brought another architectural style to the fore – Art Deco.

First developed in Paris in the early 1900s, Art Deco became fashionable and a popular choice of architectural style for “modern”, progressive businesses such as cinemas, factories, airports and power stations, as well as more established sectors like theatres, hotels and department stores.

Interestingly, London’s interpretation of Art Deco differed from some other major capitals that embraced the movement, such as New York, where materials like glass, vitrolite and chromium were used. In London, traditional Portland stone was fashioned into Art Deco’s groundbreaking forms, creating a singular and distinctive expression of the style that blended the old with the new. It was also a period of renewal and replacement – often to vocal opposition as the UK’s preservation movement gained momentum.

The demolition of most of the Adelphi Terrace, built by the Adam brothers in the late 1700s, caused an outcry, with the original structure replaced by an office block called the Adelphi Building. With its monumental Portland stone façade regarded as a classic example of Art Deco architecture, the Adelphi Building is now itself protected as a Grade II Listed building.

Along with the Bank of England, the Adelphi Building is considered one of the landmark structures of the inter-war period and Thomann-Hanry® have been privileged to clean both in recent years.

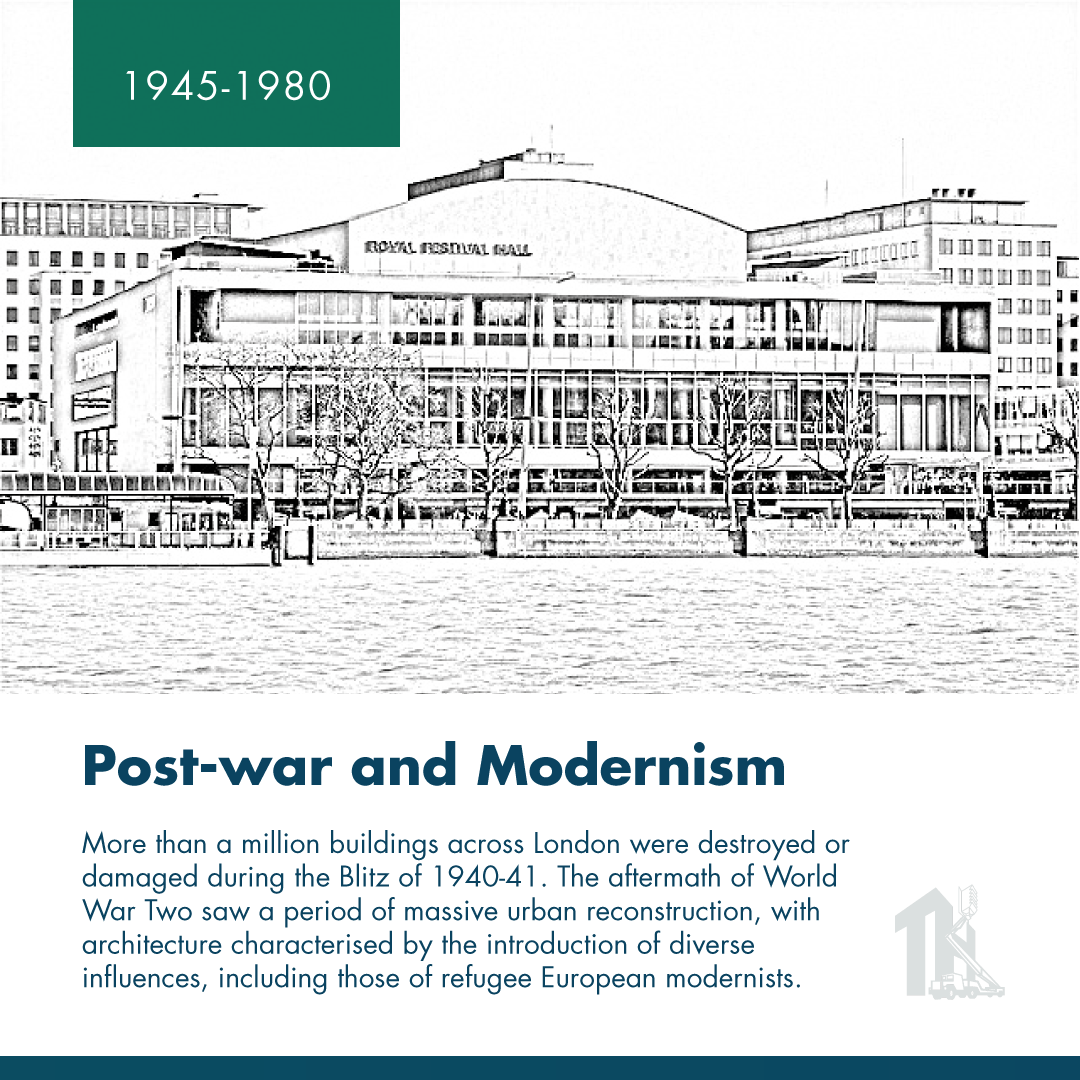

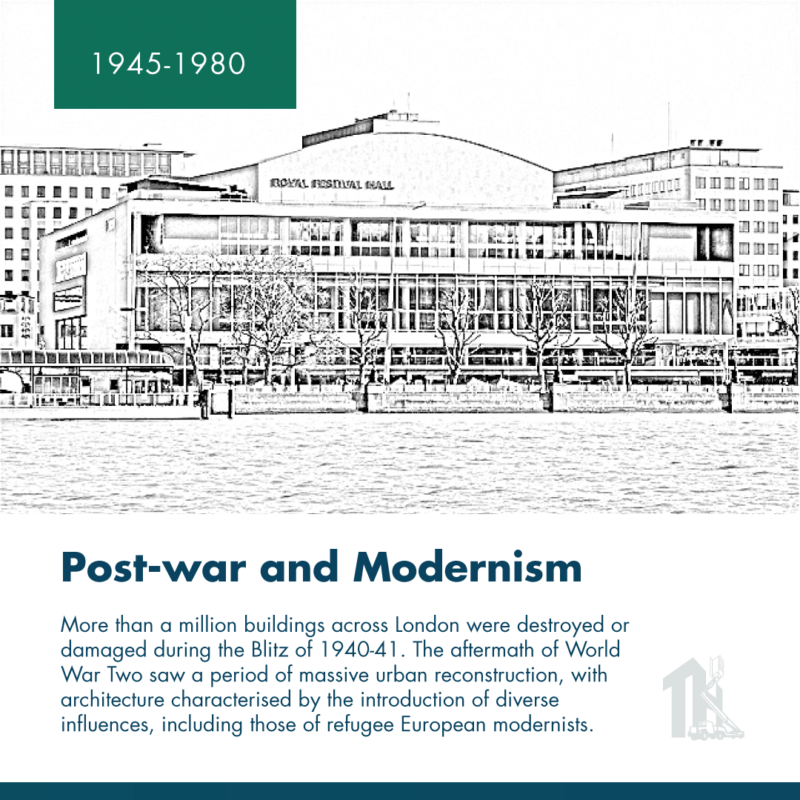

Post-war and Modernism

1945-1980

More than a million buildings across London were destroyed or damaged during the Blitz of 1940-41. The aftermath of World War Two saw a period of massive urban reconstruction, with architecture characterised by the introduction of diverse influences, including those of refugee European modernists.

Led by the work of Berthold Lubetkin and Erno Goldfinger, London’s rebuild was characterised by austere, brutalist architecture, featuring repetition of forms and widespread use of raw concrete. Heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, high rise developments were widespread in the rush to house the masses, with the likes of Trellick Tower and Balfron Tower now regarded as classic examples of the form. After many years of negative perceptions, modernism has undergone something of a re-evaluation in recent times.

The movement is also responsible for some of London’s leading post-war landmarks, including the Royal Festival Hall, at the heart of the South Bank Centre, Europe’s largest centre for the arts, and The Economist Building in St James’s. From a restoration perspective, modernism’s material of choice, concrete brings its own set of challenges.

Highly durable, it lends itself to more aggressive cleaning techniques, such as chemical and water-based processes. However, concrete has inherent drawbacks for access and scaffolding. façade gommage® is a totally scaffold-free solution, carried out from an agile hydraulic boom that can access up to 14 storeys high and achieving comparable, if not better, results than conventional alternatives.

Post-modernism

1980-present

The latest epoch of London’s history of architectural echoes and reactions, post-modern architecture has pushed back against the post-war austerity of modernism. Ironic, playful, even eccentric, post-modernism gleefully borrows and quotes from historical styles.

With glass, steel and high tech production techniques to the fore, London has seen an explosion of neo-futurist architecture over the last four decades. On structures such as the iconic Lloyds Building, utilitarian and structural elements and processes, usually hidden away, have been subverted as exterior decorative elements. As a movement, post-modernism has endowed London with some truly global landmarks, including The Shard, City Hall, 30 St Mary Axe (“The Gherkin”) and One Canada Square.

And yet, amongst all this innovation, some reassuring fundamentals have remained… constructed some 370 years after the Banqueting House was built in Stuart era London, Robert Venturi’s Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery features Portland stone.